Although we make exceptions, Straight, No Chaser is not in the opinion business. The primary goal of this blog is to provide you with factual and easily understandable information covering medicine, health care, public health and other relevant areas. We want to empower you with information and advice that allows you to be a better decision maker when it comes to matters of your health and wellbeing.

To that end, this series on child abuse has generated a lot of passionate responses without necessarily much in the way of contrary factual information. I would suggest that’s because there isn’t any. The rebuttals to the challenge to learn a better way in preventing damage to children – either through outright child abuse or corporal punishment that has unintended consequences – has been emotional and has either made readers incredibly defensive or (we hope) reflective about what we’re actually doing.

We’ve heard it all this week.

- “No one is going to tell me how to raise my child!”

- “My parents spanked me, and I turned out fine!”

- “I discipline my child so the police won’t have to!”

- “Any striking a child should be a crime.”

- “Children are the only people you can legally hit in this country!”

- “You can’t even get away with hitting a dog like you can a child!”

It bears repeating: the point of Straight, No Chaser has never been to dictate your actions but to give you accurate information that empowers you to make better decisions. Regarding parenting, spanking and child abuse, we have provided you with several posts, including the following:

Straight, No Chaser: The Physical Signs of Child Abuse

Straight, No Chaser: The Emotional Signs of Child Abuse

Straight, No Chaser: Abusive Head Trauma aka Shaken Baby Syndrome

Straight, No Chaser: Learning the Risks and Signs of Abusive Head Trauma

In this final post of the series, we press our advantage of being factual; we review the public health landscape and bring you up to date on the latest facts and evidence on the questions at hand.

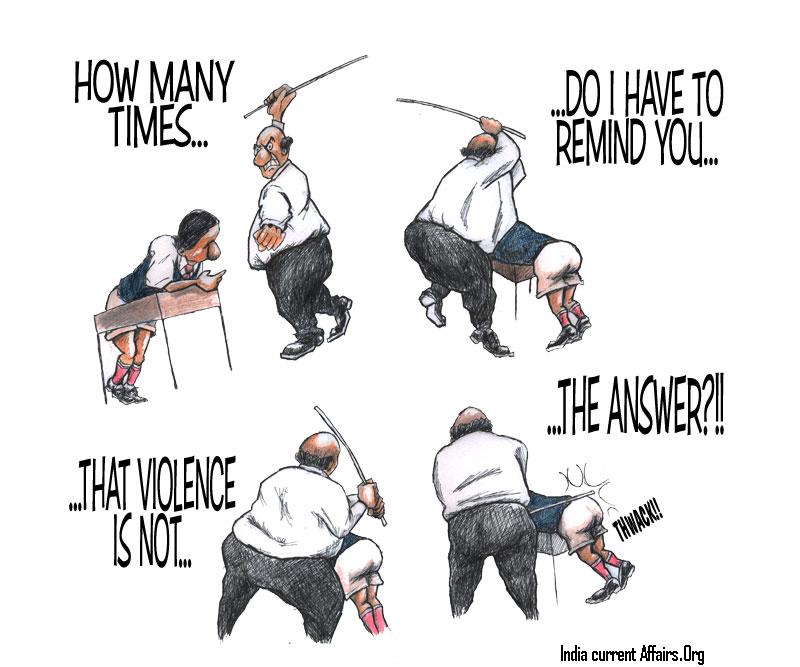

To the question: “Isn’t corporal punishment a regional and cultural phenomenon?”

Facts:

- Affluent families at the upper end of the socioeconomic scale spank children the least.

- Middle-class parents tend to administer corporal punishment in greater numbers than the affluent.

- Lower-class parents tend to do so with still greater frequency.

- African-American families are more likely to practice corporal punishment than white families.

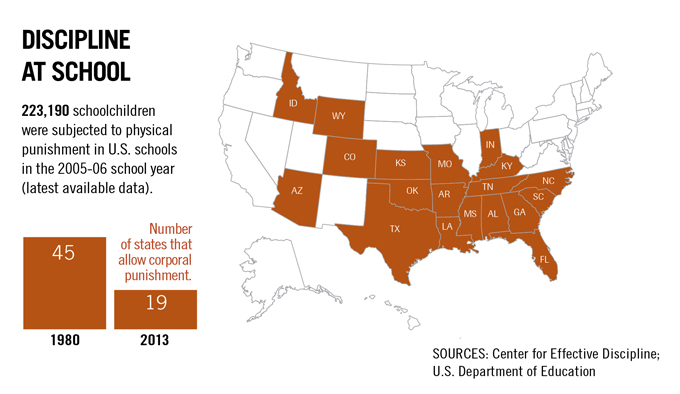

- Corporal punishment in public schools have in fact been outlawed in most of the country outside of the South (see above graphic. It is concerning and worth study to analyze whether it is more than a correlation that states with the highest rates of students obtaining advanced educational degrees are found in those states that do not allow corporal punishment in schools).

To the assumption: I have the right to raise my child as I see fit.

The line between permitted corporal punishment and punishment legally defined as abuse varies by state and is intentionally not clear. Laws typically allow “reasonable force” and “non-excessive corporal punishment.” In other words, you have the opportunity to discipline your children using your discretion. That said, if you are discovered to have crossed a line of “reasonable force” as determined by those in the system designed to review cases and protect children from abuse, you will be prosecuted. This is exactly what is unfolding in the case of Adrian Peterson, football player for the Minnesota Vikings.

Your well-intentioned spanking that turns into child abuse is not like a parking ticket; you shouldn’t expect to get a warning. Mandatory reporting laws require that persons witnessing certain visible injuries along with reports by a child of abuse to report it to the local Child Protective Services (CPS) or equivalent agency charged with the protection of the child. Such agencies operate on definitions of child abuse provided by each state’s health department. These definitions are often very different from the exceptions provided in the criminal code and often include ability of these entities to act decisively without further engaging the legal system.

To the belief: Physically disciplining my child will make them better.

The data on this question represent over 60 years and approximately 90 research studies, including summary analysis of all the data collected. In other words, this is the stuff of scientific review, not opinions.

Let me begin by sharing evidence that the above assumption is correct. This evidence is pretty much limited to one consideration. Corporal punishment does appear to reduce the short-term risk of repeating certain undesirable behaviors.

Now to the avalanche of evidence to the contrary:

- Several very prominent past and current behavioral psychologists view corporal punishment as a form of abuse. This view is based in the notion that when children are beaten during their first years of life, it physiologically creates negative and irreversible brain damage and psychologically, it negatively restructures when the brain learns. (e.g. violence as a means of problem solving is “good” or “necessary”)

- The child psychology literature reports that children who receive corporal punishment are more likely to be angry as adults and are more likely to use spanking as a form of discipline, approve of striking a spouse, and experience marital discord.

- The child psychology literature reports that older children who receive corporal punishment may resort to more physical aggression, substance abuse, crime and violence.

- The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) in an official policy statement states that “Corporal punishment is of limited effectiveness and has potentially deleterious side effects.” In particular, the AAP believes that any corporal punishment methods other than open-hand spanking on the buttocks or extremities “are unacceptable” and “should never be used.”

- Both the child psychology literature and the AAP report spanking has been associated with higher rates of physical aggression, more substance abuse, and increased risk of crime and violence when compared with older children and adolescents.

- 2012 research published in the AAP medical journal Pediatrics showed an association between harsh corporal punishment by parents and increased risk of a wide range of mental illness. Even more convincingly, this research pointedly excluded subjects who had received a formal designation of “abuse.”

- It was previously mentioned that corporal punishment was associated with less long-term compliance. However, corporal punishment was linked with nine other negative outcomes, including increased rates of aggression, delinquency, mental health problems, problems in relationships with their parents, and likelihood of being physically abused. Depression in adolescence is also another negative outcome of corporal punishment in adolescence because of the harsh punishments.

- The AAP also argues that a problem with the use of corporal punishment is that, if punishments are to maintain their efficacy, the amount of force required may have to be increased over successive punishments, a principal supported by behavioral psychology. They assert: “The only way to maintain the initial effect of spanking is to systematically increase the intensity with which it is delivered, which can quickly escalate into abuse.” Additionally, the Academy noted that: “Parents who spank their children are more likely to use other unacceptable forms of corporal punishment.” In other words, the subset of those committing child abuse is likely to come from those spanking their children.

What does this mean in terms of the role of spanking in disciplining children? Well, you’re their parents, so you retain the ultimate decision in what you do within your homes, but here’s some perspectives to let you know where the standard of care has moved.

- A 1996 AAP Consensus Conference concluded that spanking should never be used under 2 years of age because of the risks of abusive head trauma. The conference suggest that spanking may be effective for preschoolers when combined with verbal correction, and it concluded that it should not be used in older children and adolescents. Of course, these findings are nearly twenty years old, so the next update is likely to be even more conservative.

- The National Association of Social Workers “opposes the use of physical punishment in homes, schools, and all other institutions where children are cared for and educated.”

- 38 countries around the world have banned corporal punishment. The US has not.

On another level, this is largely about cognitive dissonance. No one is suggesting you’re a bad parent because you’re engaged in behaviors that have been passed on for generations and appear to have built strength and character. Just as different treatments for diseases evolve over time, open your mind to at least thinking through the facts presented to you to determine if you still think this is the best course of action for your children. Of course, your reading this blog suggests that you are that open-minded.

To the concern: Of course you’re thinking “So what’s the better way to discipline children?”

That’s the topic for another blog down the road, but here is what we do know from child and behavioral psychology:

- Human behavior is better modified by positive reinforcement than negative reinforcement or punishment.

- Human behavior is better modified by both positive reinforcement and negative reinforcement than by punishment.

Let’s make sure your behaviors reflect your desire to teach your children rather than express your anger.

Thanks for liking and following Straight, No Chaser! This public service provides a sample of 844-SMA-TALK and http://www.SterlingMedicalAdvice.com (SMA). Enjoy some of our favorite posts and frequently asked questions as well as a daily note explaining the benefits of SMA membership. Please share our page with your Friends on WordPress, on Facebook at SterlingMedicalAdvice.com and on Twitter at @asksterlingmd.

Copyright © 2014 · Sterling Initiatives, LLC · Powered by WordPress